Back in 2014, when I just started working at Booking and was still incredibly naive, I used to care a lot about what job title someone had in another part of the organization, especially outside of technology.

It felt unfair that I was leading an entire team and being called Team Leader when someone else with less responsibility might get the title of manager or *gasp* director in another organization.

Since then I changed a lot my point of view on titles, especially about comparing engineering titles across functions or different companies:

It’s ok for different functions to have different subcultures and different titles. Especially if you compare Sales vs Engineering, the different ways we handle titles or compensation make it like comparing apples and oranges.

Different companies use titles differently, technology isn’t mature enough to have a codified list of titles like finance and there’s no point in comparing.

But I was onto something, just didn’t realize it yet.

Titles are useful

I don’t want to make you believe I despise job titles. I think they are pretty useful in an organization as long as they are used correctly:

They are functionally connected to the role that the individual plays in the organization and are not used as a reward mechanism to increase salaries or benefits (use a separate mechanism for that)

They are descriptive so that by knowing your title anyone internally and externally can understand your role in the organization

They are consistent inside the same function, no different titles are given to two people that do the same job or the difference represent some kind of specialization in the same role

The Curse of Elite Overproduction

If you want to read the textbook definition here’s the page on Wikipedia.

Elite overproduction is a concept developed by Peter Turchin, which describes the condition of a society which is producing too many potential elite-members relative to its ability to absorb them into the power structure […] this situation explained social disturbances during the late Roman empire and the French Wars of Religion, and predicted in 2010 that this situation would cause social unrest in the United States of America during the 2020s.

In companies elite overproduction manifests itself in a couple of different ways:

a company goes through a phase of high headcount growth (sometimes called hypergrowth) and a lot of people get promoted very quickly and multiple times. Then the company hits a slump or reaches a size in which headcount growth becomes more “reasonable” but all those people are used to being promoted often or will (rightfully or not) leave the company

some executive decides that is time to “level up” the organization and wants to hire some big shot from FAANG or whatever is the equivalent fancy acronym of the day. But that person will not come unless they get a title higher than the one they are offered and can make some hires.

Some managers take the easy way out: create more roles in the organization.

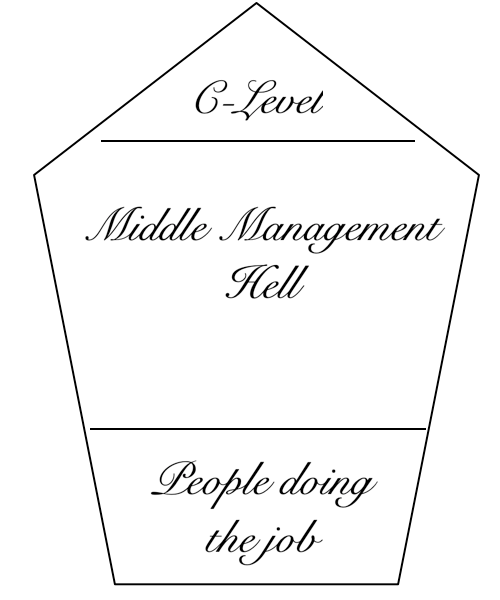

The pentagonal organization

More roles than the growth allow means that each role must have a reduced scope both in terms of people/teams and business impact.

This is bad because it creates a runaway effect:

less scope → a lot more dependencies on each other → a lower ability to deliver meaningful work → less room to be promoted based on impact on the business → promotions based on ability to navigate the politics of the organization → empire building → even less scope for others

This creates an environment in which incentives are misaligned between the business and the people running the business. This will go on until the business is damaged enough that the board will ask for a mega-super-big reorganization and a few executives will get a golden parachute while the others get a layoff. If attrition didn’t already take care of that.

Let me use another example from this great article on the topic:

early in ancient empires, many rose in status via winning military battles, or perhaps by building new trading regimes. But later in such empires, status was counted more in terms of your connections to other statusful people. Which led to neglect of military success, and thus empire collapse.

This disease is infectious

I have witnessed in my career this disease spread around an organization from function to function.

The scheme is pretty simple, one function (for the sake of example let’s use HR) decides to hire a VP to replace a Director that left. Initially, everyone is outraged because they don’t understand why the VP was hired, but it came from Amazon so everyone is kinda fine with it and they deserve the title given their seniority.

Then the VP creates a bunch of Senior Directors’ positions (a VP should have Senior Directors reporting no?) and those Senior Directors create Directors, etc etc.

The thing is that the HR function didn’t grow that much during this period so now everyone is a director and there is hardly anyone with a meaningful title.

Your engineering managers are mad at you now, they say that is impossible to have a career in this company and maybe they should switch to HR.

You resist, your peers resist but eventually, someone caves in another function or even in your function, at some point the floodgates open, and slowly but surely your company becomes pentagonal and a director of engineering now leads 1 senior manager that has 3 teams.

How do you fight the disease?

I am pessimistic about the possibility of curing a company from this disease, not only because you need the political power to get rid of the leadership that caused the issue in the first place, but then your best shot is to have a “hard reset” rebase all titles and do a mass reorganization.

An amputation of the infected part.

Are all big companies doomed then?

Only the ones with a weak culture. The strong ones understand that:

it’s ok for people to leave a company if keeping them means destroying the culture of the company

if someone will come to your company only if they get a big title then maybe you shouldn’t hire them to begin with

Those sound like common sense, so why is so difficult?

Companies that go through a quick phase of growth tend to overlook those kinds of scaling issues that happen only at the end of this phase of growth.

If you are to believe the authors of Working Backwards, Amazon encountered more or less the same problem that I describe but solved it by creating and strongly relying on its leadership principles.

Their observation was that as the company grows it gets more difficult for someone in an executive role to understand how their success connects with the business and their execution is linked to a million dependencies across different departments.

Amazon solved it with the idea of Single Thread Leadership, a way to have strong accountability for major projects and reduce dependencies. But you can think of AWS as another way they found to get out of the hole.

Another way that you can use to solve this problem is to have a single budget for both promotions and hiring, which creates a feedback loop that forces you to be much more thoughtful about who you hire and who you put up for promotion.

But at the end of the day, every company is different, and you will have to find a way that adapts to your culture

Can this phenomena be tied to the Gervais and MacLeod cycle of the firm (too much bloat and the C-suites jumping ship)? Also cool coffin org chart, vibes like the China "coffin" population graph.